Julian Thompson commemorates the 150th anniversary of Charles Dickens’ death.

Charles Dickens died on June 9 1870, at his home in Gads Hill Place, Kent, a house, if we may judge from this passage, later collected in The Uncommercial Traveller, he had long hoped to dwell in. Great Expectations, arguably his greatest book, was written there, filled with the wild hopes and hidden fears property and worldly success can inspire even in the most gifted of us. In this extract the master of Gads’s Hill meets his childhood self as it were coming back up the road of time:

I took him up in a moment, and we went on. Presently, the very queer small boy says, ‘This is Gads-hill we are coming to, where Falstaff went out to rob those travellers, and ran away.’

‘You know something about Falstaff, eh?’ said I.

‘All about him,’ said the very queer small boy. ‘I am old (I am nine), and I read all sorts of books. But DO let us stop at the top of the hill, and look at the house there, if you please!’

‘You admire that house?’ said I.

‘Bless you, sir,’ said the very queer small boy, ‘when I was not more than half as old as nine, it used to be a treat for me to be brought to look at it. And now, I am nine, I come by myself to look at it. And ever since I can recollect, my father, seeing me so fond of it, has often said to me, “If you were to be very persevering and were to work hard, you might some day come to live in it.” Though that’s impossible!’ said the very queer small boy, drawing a low breath, and now staring at the house out of window with all his might.

I was rather amazed to be told this by the very queer small boy; for that house happens to be MY house, and I have reason to believe that what he said was true.

On 8 June 1870 Dickens put in a full day’s work in his writing-Chalet at Gad’s Hill. He was writing The Mystery of Edwin Drood, his fifteenth novel and his first for five years. The book was going well, and his output that day a strong mixture of light and shade. He always felt he wrote best when he wrote in contrasting streaks, like a side of bacon. The final pages describe dark shadows of the ‘evil one’ on the misericords of Cloisterham Cathedral (based on nearby Rochester); but they also shine with the glories of early summer in the garden of England, ‘scents from gardens, woods, and fields, – or rather, from the one great garden of the whole cultivated island in its yielding time.’

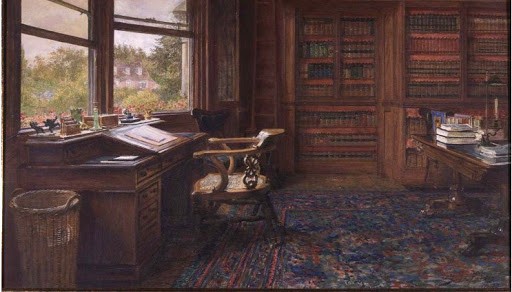

After returning to the house, Dickens, who looked unusually grey and weary, though he never looked good these days, and much older than his fifty-eight years, suffered a massive stroke at supper. He fell to the floor, muttered his last words, ‘on the ground’, and died the next day, surrounded by his family. Immediately the coveted house on Gad’s Hill was thrown into consternation, as Dickens’ wife and mistress, who were not keen on one another, needed to be granted separate audiences with his deathbed. There needed to be time for sketches of the England’s greatest novelist as he breathed his last, made by England’s most fashionable painter, Millais, arrangements for burial in Westminster Abbey (against the novelist’s private wishes), and the Graphic illustrator to size up Dickens’s empty chair:

Sir Luke Filde’s famous watercolor shows everything ready for work on the morning of, as it were, 10 June 1870, awaiting the arrival of the Master: the prematurely aged novelist, worn out by the energy of composition and the cares of living a double life; but also bumptious young Boz with his ringlets and flashy waistcoats; and even the ghost of that ‘very queer small boy’ – not to mention the multitude of characters they created and sustained. ‘The Empty Chair’ is one of the great still-lives of literature. It has been empty one hundred and fifty years this week.